Theatre of Place: The Medicine Show

Ben Gonio, Ogie Zulueta, and Mario J. Yates in Ziggurat Theatre Ensemble’s The Medicine Show

The audience was led deep into the woods, cut off from anything recognizable, with no lights visible from buildings or houses - complete darkness in the middle of nowhere.

That is the stuff of horror movies.

Photo by Rosie Sun, courtesy of Unsplash.

I’ve done Ziggurat Theatre Ensemble’s The Medicine Show three separate times. I’d like to do it again. But it’s a play that is supposed to take place in the middle of the woods at night. That can be a tall order when trying to find a space. And also for a way for the audience to know where it is, and yes, to park their cars.

The first time we did it in 1994, it was on a friend’s farm in Vermont. That performance was not too far from the house. But the house was behind the audience, and it didn’t intrude.

The second time, it was in Coldwater Canyon Park in Los Angeles in 1998. The third time was on public land in our small town in Maine in 2012. I will talk about the second time.

I was trying to remember where this idea came from to create this show, but I couldn’t. I never saw a show in the middle of the woods. Following a performance in a small village in Poland that I attended, the audience was led through a dark wood by torchlight to where the reception was. There was no performance outdoors, but even that procession had its elements of theatre and ritual.

The unmasked night is a contemplative time.

Wallace Shawn and André Gregory in My Dinner With André, directed by Louis Malle.

I do remember in the movie My Dinner with André, André Gregory described doing paratheatrical work in the woods with Grotowski. Gregory also talked about gathering with friends on Montauk on All Soul’s Eve for another paratheatrical event on Richard Avendon’s property. In the middle of the night, three friends led them deep into the woods to a place where graves had been dug. Gregory and the others were each blindfolded, lowered into a grave, covered with a sheet and then some dirt was shoveled over them. After remaining there in the grave for a half an hour, they were lifted out and resurrected. And everyone danced until dawn.

Was that a true story? I don’t know. But it was described as if it was. And it might have influenced my creation of a play where the entire audience was in the woods and cut off from familiar surroundings.

And now, a commercial:

Historically, a medicine show was a traveling show which toured the old west during the 19th century. There were sharpshooters, jugglers, magicians, singers - anything to attract a crowd. Between acts they would peddle bottles of “patented” miracle cures. Not only were these bottles not miracles, they were not even cures. Some of them were even harmful.

And now, back to our show.

We had arranged for the audience to gather in the parking lot adjacent to Coldwater Canyon Park. The audience got out of their cars and were asked to remain in the parking lot until we were ready to “take them.” There would be no late seating.

When it seemed like the entire audience had arrived, a member of the company led them on a 15-minute walk into the woods. This walk was a crucial part of the play. The act of leaving “civilization” and journeying into the woods, slowly prepared the audience for what they were going to see. Fifteen minutes is not an insignificant walk when there is no light but flashlights and you don’t know exactly where you are going to end up. And the imagination of the spectators could move slowly from the known to the unknown.

From Philip Brandes’s LA Times article:

“Pushing the theatrical envelope toward a more complete immersion in the exploration of cultural wellsprings is the continuing goal of Ziggurat artistic director Stephen Legawiec. Here, the assembled audience is escorted en masse by flashlight-bearing guides down a rustic trail – not a strenuous trek, but far enough to sever us from the context of contemporary civilization.”

Once again, as in The Cure, the audience was going to see something which had the illusion of a real event. There would be no curtain speech.

Gradually, as the audience walks, they can see light pulsing in the distance. We had lit the playing area with Coleman lanterns and behind one of them was the character of the driver, the empresario, the master of ceremonies of the Medicine show.

That role was played by me.

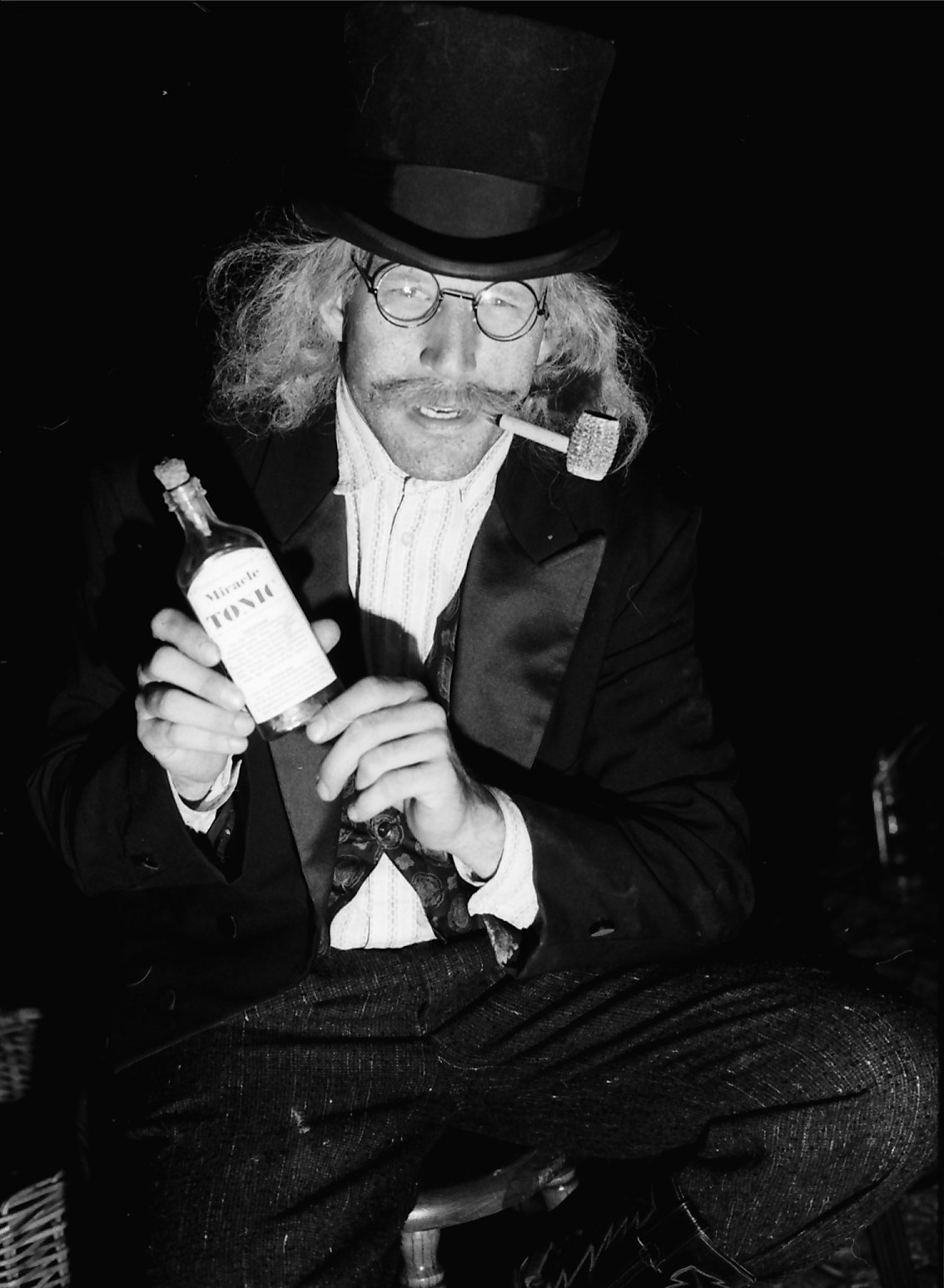

The author, in a wig and false mustache, hawking a bottle of “Miracle Tonic.”

Once the audience arrives, the Driver explains about the historical medicine show and makes the point that “This will be a real medicine show.” He then goes on to say that his troupe can’t do the show because all of the performers are sick.

The Driver then describes the show that they were going to do, a Native American tale about a boy who battles demons; a boy who is wondering through the woods with a lantern. At that moment, a light is seen as a pinpoint, far away in the darkness. The driver says, “But it’s too bad that you came out all this way. Because there aint gonna be no show.”

And then the show begins.

The audience watches the light come closer and sees that it is a lantern held by the boy who stumbles upon the stranded troupe. He decides that demons are causing the sickness – the same demons that plague his dreams. He goes to sleep and enters his dream world in order to battle the demons and cure the troupe. The demons are dispelled, but in the process the boy dies. The actors, now cured, perform a ritual which brings the boy back to life. And everyone, including the audience, dances.

Tonilyn Hornung, Constance Hsu, and Beverly Sotelo. Ogie Zulueta in the background

In The Medicine Show we wanted to provide a mythic experience from a distinctly American point of view. As Americans we do not have a culture as do, say, the Greeks, which can be traced back thousands of years. Still, there are things about which a mystique has arisen, and which are endowed with qualities larger than themselves. One of these is the "Old West."

“The Birds” dance at the end of the show.

Left to right: Tess Borden, Ogie Zulueta, Ben Gonio, Constance Hsu, Alyssa Zulueta, Beverly Sotelo, Mario J. Yartes, Tonilyn Hornung. Stephen Legawiec in the foreground

From Steven Leigh Morris’s LA Weekly review:

“Talk about transporting. From the parking lot of Coldwater Canyon Park, guides with flashlights lead the audience down a dusty trail to the rustic stage and audience bleachers. On the night I attended, a shroud of fog was pierced by a quarter moon. A 19th century, top-hatted, bespectacled Driver (writer-director Stephen Legawiec) sits at a work-bench, crooning ditties in front of a billboard that advertises a performance of The Birds, a "Navajo Indian story culminating in a festive dance." But there’s no show, Driver explains. The actors are all backstage, dying from a strange malady. A French-speaking prop girl (Alyssa Lupo) appears, as Driver shows us a puppet he’s building, which represents a wandering boy who can’t sleep from being tormented by demons. "Maybe he’ll carry a lantern," Driver ponders, just as we see a lantern on a distant hill carried by a Boy (Ogie Zulueta), who passes behind the billboard and onto the stage, and in sign language begs the prop girl for some food. Indeed, gibberish-speaking, choreographed masked spirits torment him, accompanied by haunting a cappella chorals, culminating in the Navajo Dance of the Birds – all within an hour. Legawiec, among the most idiosyncratically visionary directors we have, picks up where he left off with his The Cure, offering a partly invented, partly researched anthropological theater that’s as memorable for its winking wit and raw beauty as for its mesmerizing power. Leave logic at home. The Medicine Show speaks in truths that are part tribal, part Jungian. Miss it at your cost."