Three-point Perspective: A Cult of Isis

Looking back over the plays that I’ve written, there are certain themes which come up again and again. One of them is parallel scenes. Show a scene once and then show it again in a different way.

I did this first in a play called Ninshaba which was a story based on ten fictional ancient tablets. There were two versions of tablet nine, which were slightly different, and we dramatized both of them, one right after the other. The second version was more dramatic than the first.

Parallel scenes go back to the Epic of Gilgamesh, but perhaps more famously in the synoptic gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, which are not completely “synoptic.” They purport to tell the “same” story of Jesus’s life.

In Waiting for Godot, Didi and Gogo are discussing the gospel discrepancies, when talking about the thieves at the crucifixion.

VLADIMIR

How is it that of the four Evangelists only one speaks of a thief being saved. The four of them were there—or thereabouts—and only one speaks of a thief being saved.

ESTRAGON

(with exaggerated enthusiasm). I find this really most extraordinarily interesting.

VLADIMIR:

One out of four. Of the other three, two don't mention any thieves at all and the third says that both of them abused him.

ESTRAGON:

And why not?

VLADIMIR:

But one of the four says that one of the two was saved.

ESTRAGON:

Well? They don't agree and that's all there is to it.

Roshoman Poster

Rashomon (Kurosawa’s 1950 movie based on the short story “In a Grove”) also does this. Various people describe how a samurai was murdered in a forest. The same scene is shown again and again through each person’s particular point of view.

I’ve written parallel scenes in several plays. It’s one of the things I must be preoccupied with because I keep doing it. (I don’t know why.) Ziggurat Theatre Ensemble’s A Cult of Isis is the quintessential example of that. The entire plays is parallel scenes. Here is its strange source:

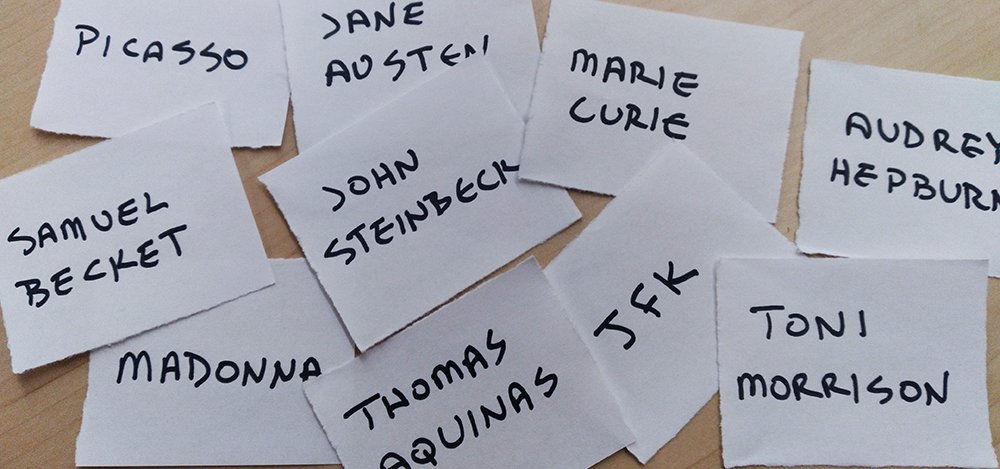

We used to play a guessing game at parties. There were two teams, and you had ten pieces of paper, each with the name of someone famous.

You would then describe each person to your team, saying whatever you wanted, so that your team would try to guess the names.

That was round one.

Next you would try to have your team guess the same ten names, but this time you could only use one word for each.

That was round two.

Finally, it was again the same ten names, but now you could only use one gesture per name.

That was round three.

But here is what is important about the game. Round Three would be impossible without Round Two. And Round Two would be impossible without Round One.

Each round gives you information you need to understand the next round.

The structure of this game became the inspiration for A Cult of Isis.

Dana Legawiec (Isis) and Lyena Strelkoff (Initiate)

in Ziggurat Theatre Ensemble’s A Cult of Isis

In A Cult of Isis, we enact an initiation ritual from a fictional ancient Goddess cult. The audience sees the ritual performed three times.

The First Time:

The five human participants speak in what sounds like a foreign language. The language was invented for this play. (See my post on Ninshaba for the background of my foreign language experiments.) We are clearly watching a ceremony, but of what? Behind them, two spirits, as if watching over the ceremony, appear to slowly dance. And the ritual comes to a close.

The Second Time:

Now we see the ritual performed again. And visually, the physical actions of the humans and the spirits are the same. But this time the five participants mouth silent words, and we hear the voices the spirits: Queen Hatchepsut, who ruled Egypt 500 years previously in 1500 BC, and the Goddess Isis herself. They offer commentary about the human world, without really taking in the ritual. These spirits are only mildly interested in the mortal plane. And a second time, the ritual comes to a close.

The Third Time:

When the ritual begins for the last time, the goddesses are silent again and we finally hear the words of the participants in English. However, we discover that the cultists are not saying what we thought they were saying. It is an initiation ritual of a novice into the cult. But the initiate has coerced the cult into taking part in an elaborate scheme in order to dispose of a corrupt judge who is torturing her daughter. The initiate takes poison so that the cult members will attest that she was killed by the judge, thereby doing away with him. But she takes the poison prematurely, before the cult agrees to her plan. A debate ensues over the proper role of the cult as the woman is dying. The audience, although they have seen the ritual twice, don’t really know until the third time what they are really seeing.

On pedestals: Jennifer Chu and Naila Azad; Center: Lyena Strelkoff

Front: Valerie Spencer, Luis Ambrano, Michelle Tenazas

in Ziggurat Theatre Ensemble’s A Cult of Isis

Even before I wrote the script, I remember pitching this story to company actress Lyena Strelkoff, to see if she wanted to play the protagonist.

At the dramatic climax of the initiation scene, Lyena’s character gives a very agonizing monologue where she describes what the depraved judge does to her daughter. It was a difficult speech to write and even more difficult speech to ask the actress to deliver. She had the additional, virtually-impossible task of “going there” three times in the course of an hour. The first time, she speaks the devastating speech in a foreign language, the second time she mimes the speech, and the third time is in English. Lyena was able to pull up the painful emotion every time. It was an extraordinary performance and one of the reasons the play succeeded.

The three versions weren’t exactly identical. The English version (third time) was almost twice as long as the foreign language version (first time.) But no one noticed. Dana Legawiec’s beautiful and painstaking choreography, which was present in all three versions, sold the idea that the scenes were exactly the same.

We had these huge debates in rehearsal about whether the protagonist was right to do what she did: to join a cult just so she could compel its members to take revenge for her. The actors argued about it in rehearsal after rehearsal. It is as if this was not a play, but a real event and everyone had a passionate opinion about it. This became the moral question that the audience became complicit in. For in the play, the audience was cast in the role of congregation. Backstage described it this way:

“Because Ziggurat's newest creation enacts the initiation ritual of a young woman into an unlawful cult, and we, the audience, are cast as a congregation of subversives, writer/director Stephen Legawiec's choice of an outdoor amphitheater in Coldwater Canyon--in late October and accessible by a narrow dirt road and a brief uphill hike--makes infinite sense. Such conditions (if we experience them as fugitive worshippers) start to embody the play's concerns: the strained interplay of religious and civil communities and the discomfort of negotiating between their laws.”

In addition to the mythic aspects, A Cult of Isis explores the nature of storytelling itself. How stories are told and how our perception changes what may or may not be there. The power of parallel scenes is not that one version supplants or corrects the other. It’s that the mind holds all of them at the same time, allowing them to merge, bicker, collide and imperfectly coexist in a constant state of unrest. And that is one of the things I love about a great piece of theatre - it lives within you because it just won't sit still.

A Cult of Isis

written and directed by Stephen Legawiec

Costumes by Robert Velasquez

Movement and choreography by Dana Legawiec

Lighting by Leif Gantvoort

Masks by Beckie Kravetz

Original music by Susan Christiansen

Cast

Isis: Jennifer Chu

Queen Hatchepsut: Naila Azad

Priestess: Valerie Spencer

Priest Luis Zambrano

Initiate: Lyena Strelkoff

Acolyte: Michelle Tenazas

A Cult of Isis was first presented at the A.S.K. Common Ground Festival with the following cast: Isis (Dana Legawiec) Hatchepsut (Naila Azad) Priestess, (Jenny Woo Umhofer) Priest (Dean Purvis) Initiate (Lyena Strelkoff) Acolyte (Jennifer Chu)